By Randi Weingarten on February 11, 2016

Politics and religion have long been known for their potential to turn a conversation into a conflagration. In the last decade, education joined that short list of touchy issues. That’s no wonder, since many self-described “reformers” frame the debate around false dichotomies, such as their claim that one can’t be both pro-child and pro-teacher, or that their camp cares more about children or has a greater sense of urgency than “regular” classroom teachers and the unions that represent them. While I completely reject those propositions, it doesn’t mean that our differences should stop our discourse with each other — quite the contrary, because we can’t solve problems in education or make progress without finding common ground.

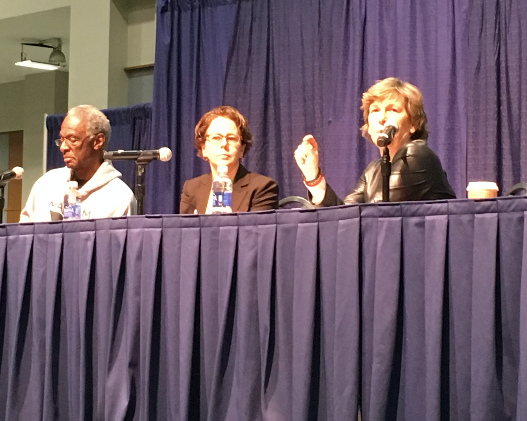

And that is what happened last weekend. Thirteen thousand people converged on Washington, D.C., for Teach for America’s 25th anniversary. Even though I have been critical of TFA, I was invited to speak about how to address both education and poverty, along with Howard Fuller, an education activist who supports education vouchers and other forms of privatization. Cecilia Munoz, the White House domestic policy advisor, moderated the discussion and kept it constructive.

I’m pretty sure a fair number of people attended the packed session to see if the discussion between two people who don’t see eye to eye — either physically (he is much taller) or ideologically (in many respects) — would descend into Fight Club.

Fuller didn’t win me over to his side, and I’m sure I didn’t convert him, either. The private school vouchers he introduced as superintendent of Milwaukee Public Schools a quarter century ago have not produced superior academic results for students who receive them, nor have they spurred public schools to improve in order to compete. Sadly, Milwaukee’s public and voucher schools perform at levels comparable to those in rural Alabama and Mississippi. And yet Fuller continues to advocate nationally for choice and privatization. But that wasn’t the point.

My purpose was not to debate Fuller; it was to have a conversation about a path forward, to end the ridiculous debate in reform circles that poverty and greater economic issues don’t matter, and to debunk the notion that individual teachers can do it all.

I caught some flack on Twitter and Facebook for even attending a TFA event. The AFT and TFA disagree on a number of fundamental issues regarding education. I believe that teacher preparation should reflect the complexity and importance of this work, and that a crash course simply doesn’t cut it — it’s not fair to corps members or their students. Further, I think that TFA’s model of inadequately prepared teachers and high turnover deprofessionalizes teaching by design. And it’s dead wrong when districts use austerity as the excuse to hire TFA recruits as replacements for experienced teachers.

I believe that teacher preparation should reflect the complexity and importance of this work, and that a crash course simply doesn’t cut it — it’s not fair to corps members or their students.

Regardless of what one thinks about TFA as an institution, I believe it’s a mistake to write off the thousands of people who, over TFA’s 25 years, have been part of its educational landscape. TFA corps members and AFT members share a deep commitment to making a difference in the lives of children. And the more time TFA corps members spend in classrooms, the more I see they have a desire for respect and dignity for the teaching profession similar to AFT members’. And frankly I’m willing to go into the lion’s den to make our best case and look for ways even unlikely allies can walk with us.

The session was premised on the fact that poverty matters. That was huge progress. And there was a hunger in the audience for the resources and the broader economic, social-emotional, instructional and diversity strategies needed to address poverty.

The session was premised on the fact that poverty matters. That was huge progress.

The TFA alums who spoke during the session didn’t buy into false dichotomies. One who taught in New York City public schools while I was president of the United Federation of Teachers even thanked me for my advocacy. Another TFA teacher spoke of the need for a union — how administrators in the Cleveland charter school where he worked posted a sign that said “Students = Money,” and that teachers feared being blacklisted or fired if they spoke up about poor conditions. When the staff started to organize a union, the management backed off, enabling teachers to advocate for themselves and their students, proving the power of collective action.

And of course there were others surprised by what a union really does (as opposed to the myths concocted expressly to undermine collective power and voice). The AFT started Share My Lesson, the fastest growing ed-tech service, which allows teachers to share lesson plans and other educational materials and best practices. The AFT has posted thousands of resources on Share My Lesson aligned to the Common Core standards to help teachers navigate this huge shift. And, after I described the AFT-led project to alleviate abject poverty in McDowell County, W.Va. (the country’s eighth-poorest county), several TFA corps members and alumni thanked me for addressing the often-ignored issues of rural poverty.

Hundreds of past and current corps members visited our Share My Lesson booth, as well as our booth with information about First Book, through which AFT members have helped thousands of kids — many who have never owned a book of their own — build home libraries. Several TFA teachers asked how to join the AFT, and a number of corps members and alums asked for help in having a voice or in organizing their charter schools. Many just whispered to me, “I’m glad you are here.”

Several TFA teachers asked how to join the AFT, and a number of corps members and alums asked for help in having a voice or in organizing their charter schools.

I was billed in the run-up to the TFA summit as being the dissenting voice in the room. But at the end of the session, it was evident that, when labels are stripped away, the common denominator is that all teachers want to be supported to do their very best for their students, and they want the bigger challenges addressed. Like so many AFT union members, TFA teachers don’t want to be blamed or scapegoated; they are fellow soldiers in the fight to address economic injustice, alleviate poverty and ensure diversity among the people who teach our children and who make decisions affecting them.

At the end of the day, we can’t bring about the sea change needed in public education by talking only with people who we think agree with us. It’s not fun being the person invited to provide the countervailing view, but I’ll keep doing it. Because I feel that the AFT and our members can provide the path forward to reclaim the promise of public education and to create public schools where parents want to send their kids, students are engaged and educators want to work. And I’ll take the fight for that vision anywhere I can.